Analysis of responses generated by global-surveys on gender equality in 2020 and 2021 conducted by Facebook finds that Covid-19 is affecting access to food and healthcare for women in India — worse than for men in India and women in South Asia. This article identifies these deprivations and recommends targeted policy interventions to address them.

BUILDING CONTEXT FOR THE ISSUES AT HAND: At a time when food and medicines need to be our lifelines to recovery and repair, the Covid-19 outbreak has exacerbated existing hunger and healthcare crises. The World Bank calculates that the pandemic will push 71 million people across the world into extreme poverty, characterised by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food.[i] In line with which, the World Food Programme estimates Covid-19 rendering 130 million people ‘food insecure’, in addition to the 820 million already classified as such.[ii] Meanwhile, the World Health Organization’s findings from 135 countries in its National pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in January-March 2021 highlights persistent disruptions at considerable scale over one year into the pandemic.[iii] With 90 per cent of the respondent countries reporting one or more disruptions to essential health services.

As is disturbingly evident therefore, the numbers cited above add up to make for a Covid-spawned context of acute food insecurity and medical care deficiency at the global scale. But even more pertinently for us perhaps, the numbers should alert us to the urgency with which we must assess the unfulfilled needs of our own population with regard to hunger and health. After all, India did drop from the 94th to the 101st position among 116 countries in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) in this year of the pandemic.[iv] Even as millions of Indians infected with the coronavirus suffered long and futile waits for hospital beds or oxygen. Because the Indian medical system has really always been unprepared for health crises, underfunded as it is with a mere $73 spent on health care per capita versus a world average of $1,110.[v]

These chronic insufficiencies apart however, given the calamitous situation at hand, the compelling need now is to identify populations in India that are most deprived of access to food and healthcare in India to design targeted and immediate programmatic and policy interventions to facilitate relief and recovery.

SOURCING DATA: Towards the mandate stated above, this article draws from results of two surveys titled ‘Gender Equality at Home’.[vi] As per Facebook, these are the initials in a series of surveys that it will conduct annually. The explicit aim of the first two surveys, meanwhile, is to provide ‘a gender data snapshot of life during COVID-19’. Designed to cover topics about gender norms, unpaid and household care, access and agency, and Covid-19’s impact on these, the first and second survey comprise 75 and 33 questions respectively.

Fielded in July of 2020 and August of 2021 in over 200 countries, the surveys report covering 461,748 and 96,054 respondents respectively.[vii] The data obtained by these surveys has been used to research and arrive at this article’s findings.

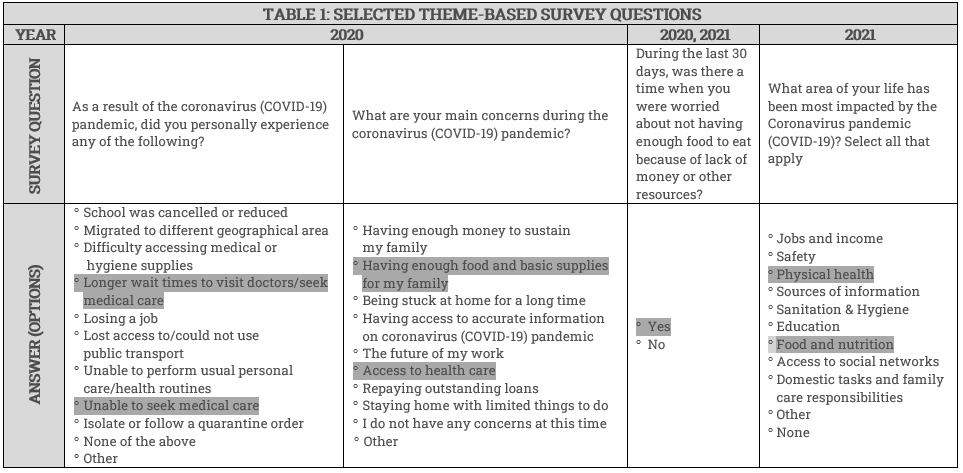

FORMULATING A STRUCTURE FOR OUR ANALYSIS: We began by studying the questionnaires of both surveys with the aim to identify queries related to the impact of Covid-19. Then, we narrowed our search to identifying such questions that offered respondents answer-options related to the two themes of our study, i.e. access to food and access to healthcare. Three and two such questions were fielded in the 2020 and 2021 surveys respectively; with one of the questions common to both surveys.

Table 1 below presents the questions with answer-options relevant to the study theme highlighted.

We then formulated a matrix such that we could track the respondents’ progression with regard to accessing food and healthcare over the two years of the pandemic, which included several debilitating lockdowns.[viii] The matrix was designed to show up how each of the two themes under study had fared vis-a-vis three dimensions: ‘concerns’, ‘experience’ and ‘impact’. Which is to say that, had indeed accessing food and healthcare turned from being the respondents’ worry and concern, to their lived experience, to finally impacting their lives? And how did men and women in India compare with regard to these dimensions? Also, did women in India measure differently on these dimensions relative to women in South Asia on the whole?[ix] The narratives that emerged are listed as our findings below.

FINDINGS

A. Access to food

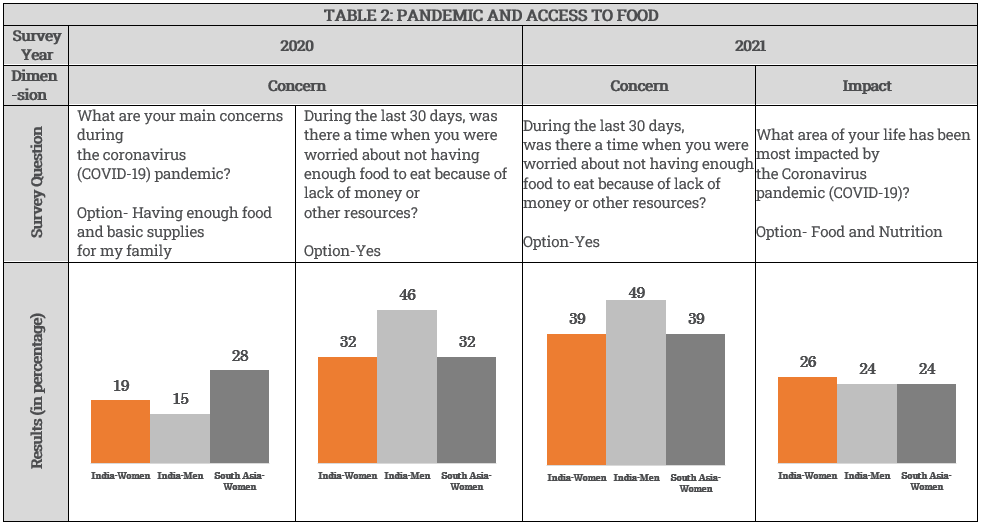

Concern and worries regarding access to food is on an increase among men and women in India, and also for women in South Asia in general. Between 2020 and 2021, all three respondent types reported being more anxious about not having enough to eat in the last 30 days (from the date they were administered the survey). While the escalation was at three percentage points for men in India, it was at seven percentage points for both women in India and in South Asia. This indicates higher intensification of anxiety over the issue for women.

To begin with, in the first year of the pandemic itself, more women than men in India said not ‘having enough food and basic supplies for their families’ was a primary concern for them during the pandemic. At 19 per cent, food insecurity during the pandemic was more likely a concern for Indian women than for men at 15 per cent.

Two years into the pandemic, show survey responses, concerns about food insecurity have turned into reality for both men and women in India. The pandemic’s effect on food and nutrition has in fact been worse than the initial worries about these. In 2020, 15 and 19 per cent of men and women in India respectively shared their concern over securing sufficient food supplies. By the end of the second year of the pandemic, food insecurity has impacted a larger proportion of respondents than those who had initially expressed concern. Twenty-four and 26 per cent of men and women respectively reported an impact on their food and nutrition, highlighting that women are more affected by food insecurity than men in India. Contrarily, meanwhile, survey responses indicate that women in South Asia have suffered lesser of an impact vis-a-vis food insecurity, than they had been anxious about. While 28 per cent women in South Asia were worried about food supplies for their family in 2020, 24 per cent say it has impacted them.

Also by 2021, food insecurity has impacted Indian women the most, compared to both Indian men and women in South Asia generally. Twenty-six per cent of the women respondents from India report having been impacted from food and nutrition as against 24 per cent of, both, men in India and women in South Asia.

Table 2 below presents a matrix that tracks the effects of the pandemic on access to food and shows the progression of respondents across two dimensions.

B. Access to healthcare

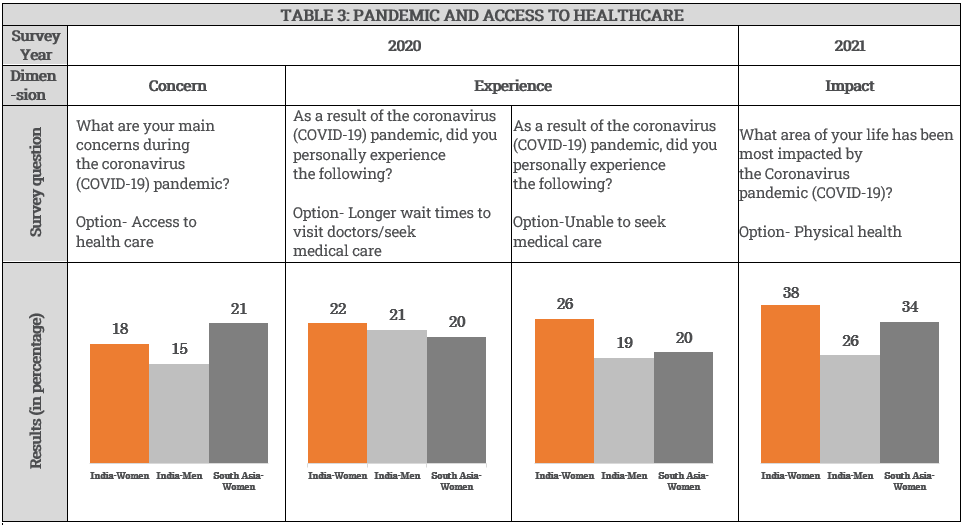

For women in India the inability to access healthcare turned from being a concern to a lived experience, finally impacting their physical health; and this progression registered an increase with each dimension. Eighteen per cent of women respondents in India expressed concern about accessing medical care in 2020. Twenty-six per cent and 22 per cent said they were unable to access and avail swift medical care respectively. These figures grew even larger by 2021, with 38 per cent women reporting that their physical health had actually been impacted.

In fact, more women than men in India expressed concern over accessing healthcare and experienced disruptions in availing swift medical care in the first year of pandemic. And, by 2021, these shortcomings have had a higher impact on the physical health of women as compared to men. While women exceeded being anxious about accessing healthcare by three percentage points as compared to men, women were seven percentage points behind in availing of it. Significantly, the impact of such insufficiency in medical care impacted the physical health of women worse than that of men by twelve percentage points.

Moreover, women in India are worse placed than women in South Asia generally in accessing medical care, both as an experience and in terms of the impact it has on their health. The differences between the experience of women in India and South Asia, in terms of inability and delays in seeking medical care stands at six and two percentage points respectively. The impact of this on the physical health is also greater on Indian women by four percentage points compared to women in South Asia.

Table 3 below presents a matrix that tracks the effects of the pandemic on access to healthcare and shows the progression of respondents across three dimensions.

RECOMMENDING TARGETED POLICY INTERVENTION: Our analysis above finds evidence that the pandemic has been the harshest on the physical health of India’s women. It has caused them increased stress about being unable to procure food and medical services for themselves and their families. They have had to suffer delays in seeking and availing timely medical care. Lack of adequate nutrition and food has been an added burden. And while some of these hardships are the pandemic-intensified outcomes of chronic scarcities that India suffers, they need to be remedied immediately before they flare uncontrollably fueled by the current health crisis.

Towards this, research exercises aimed at locating the most vulnerable among our population in these times of the pandemic is critical to our survival and recovery. Once identified, a mix of quantitative and qualitative methodologies can be employed to further understand the peculiarities of the needs of such deprived identities. And the information and insights so obtained can be used to inform targeted programmatic and policy interventions to strategise urgent outreach and aid.

Soma Wadhwa (swadhwa@idfresearch.org) is Fellow and Tanya Bansal is Research Assistant at the India Development Foundation.

[i] World Bank. 2020. Global Economic Prospects, June 2020. Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33748

[ii] World Food Programme (WFP). 21 April 2020. WFP Chief warns of hunger pandemic as COVID-19 spreads (Statement to UN Security Council). https://www.wfp.org/news/wfp-chief-warns-hunger-pandemic-covid-19-spreads-statement-un-security-council

[iii] World Health Organization. (2021). Second Round of the pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: January-March 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS-continuity-survey-2021.1

[iv] 2021 Global Hunger Index. https://www.globalhungerindex.org/india.html

[v] World Bank. 2018. Current health expenditure per capita (current US$)-India, World. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.PC.CD?locations=IN-1W

[vi] Survey on Gender Equality at Home Report (September 2020 and November 2021): dataforgood.fb.com/tools/gendersurvey

[vii] Gender wise break-up of respondents is available only for 2020: 160,637 men and 152,040 women.

[viii] The lockdowns in India were especially severe. There were four nationwide lockdowns in 2020 in the months of March, April and May. In 2021, there were more than 15 state-wide lockdowns from March to approximately June. The mass displacement of migrant workers during the lockdowns became a major issue. According to the Union Labour and Employment Ministry, over 11.4 crore (11 million) inter-state migrant workers returned to their homes during the March 2020 lockdown.

[ix] Respondents in the surveys for South Asia include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal and Pakistan.

The views expressed in the articles published on this microsite are those of their authors. The articles are not peer reviewed. While we have made sincere attempts to verify the facts presented in the articles published here, we do not vouch for their veracity or accuracy.