Mobility data could be a game changer in tracking the Covid-19 spread. Our analysis of high-frequency real time mobility data from Facebook and Google shows that continual monitoring of changes in the usual behaviour of people can help contain the pandemic.

Any disaster, or crisis, hits different people and different parts of the country differently. In a pandemic like the one we are going through now, the virus spread needs to be monitored continually to forecast where and when it will hit so that adequate preparations can be made to mitigate its effects. Waiting to observe the where and when before rushing in relief could lead to feeding the spread rather than stopping it. This is where high frequency real time data can be extremely useful, especially if this data reflects how people are responding to information that they receive before it reaches the administrative machinery.

Suppose we know that people move daily from A to B to go to work during the day and return home from B to A in the evening. If one looks at the Facebook mobility data, it is immediate that mobility had come down significantly before March 25, 2020, when the first lockdown started last year. Without such mobility data, there would have been no other way to observe this phenomenon unfolding on a daily basis. This change in people’s behaviour could be interpreted in two ways. One would be to think that responsible and aware people cut down on their mobility while the irresponsible and reckless ones continued with life as usual. Another, and less arrogant, interpretation could be that those who could stayed home, those who could not had to move around.

Both interpretations could be right as both responsible and irresponsible persons make up societies. But if we believe that, on the average, people are self-motivated, then it follows that the second interpretation is a better starting point to policymaking than the first. Why? Because it tells us that policymakers need to focus on containing the spread among people who, because of livelihood necessity, are forced to move.

If we continue to trust our citizens as responsible adults, the real time mobility data shows us yet another way to contain the spread. Administrative information, by definition, is aggregated by administrative units --- by blocks, by districts, etc. The spread of the Covid-19 virus, however, happens from individual to individual. It, therefore, depends on contacts among people in the neighbourhood and in the workplace, both much smaller than the geographical space of a block or a district. In other words, neighbourhoods learn of the potential risks, from observed incidents as well as word-of-mouth information from close societal neighbours. The spread from one block to another block, or one district to another district is essentially because of the movement of the people between these two districts. While the administrator waits to aggregates active cases, people who are affected by it, their friends, relatives and everyone else they communicate with, respond immediately to this information. It is in their interest to avoid being infected and one way they can do that is reduce their avoidable mobility. Their behavioural response, reduced mobility, to this “local” information could act as a signal of ground realities if the policymaker were to follow the mobility behaviour.

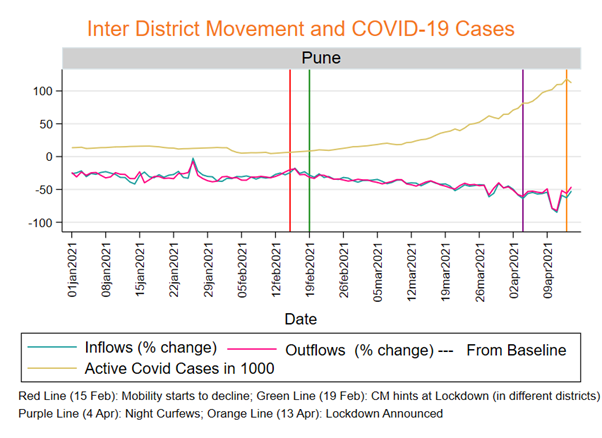

A simple example highlights this idea. To counter the spread of the virus in Pune, the administration announced on 13 April, that a lockdown will take effect from 14th April, 8 PM. In the diagram, we have plotted the daily rise in active cases (in 1000s) in Pune and the daily mobility of people moving in and out of Pune (as a percentage change from the baseline last year). Observe that mobility starts declining from 15 February, almost a full 60 days before the lockdown is even announced! It is not important if the lockdown works or not; the point being made here is that if the lockdown works, it would have worked better if it was announced closer to 15 February. In fact the first time a lockdown was hinted at – not in Pune but districts in Vidarbha region – was on 19 Feb, after mobility had already started declining.

This behaviour does not limit itself to Pune. More rigorous analysis, carried out in a research study using Facebook mobility data by the India Development Foundation, shows that similar results hold for all of Maharashtra during this period. In fact, in our countrywide analysis of mobility, ever since the virus hit India last March, we have uniformly found a negative relationship between Covid-19 spread and mobility. People respond to the rising risk of infection by reducing their mobility. Why does mobility not fall to zero? This is because not everyone can work from home. Second, ordering online means someone has to deliver the goods to the homes. Third, essential workers, casual labour and all those who have lost their erstwhile jobs will have to keep searching for jobs to maintain their family. So people move around not necessarily because they are irresponsible, but because they are responsible to others.

An important inference that could be drawn from our analysis of the mobility data (available from Facebook and Google) is that people are responsible but they need to have information. Greater is the transparency and speed at which cases are made public, easier it is to contain the spread. Use whatever data are available, from government or private entities, especially if they are of high frequency and real time, to continually monitor changes in the usual behaviour of people. These could be useful early warning signals.

(Acknowledgement: This paper has used Facebook mobility data)

Nishant Chadha (nchadha@idfresearch.org) is Head-Projects and Shubhashis Gangopadhyay is Research Director at the India Development Foundation.

The views expressed in the articles published on this microsite are those of their authors. The articles are not peer reviewed. While we have made sincere attempts to verify the facts presented in the articles published here, we do not vouch for their veracity or accuracy.